Compendium of Data Structures

Graphs

Graphs are data structures composed of a set of objects (nodes) and pairwise relationships between them (edges). Notably, edges can have properties, like a direction or a weight.

Graphs can be represented as:

- Adjacency matrices: matrices in which every row \(i\) contains the edges of node \(i\). Specifically, \(\text{row}_{ij}\) is 1 if nodes \(i\) and \(j\) are connected, and 0 otherwise. They are symmetric for undirected graphs.

- Adjacency list: list of pairs, each of which represents an edge by describing the two involved node indexes. The node order can be meaningful (in directed graphs) or not (in undirected graphs).

- Hash map: keys are node ids, values are the set of nodes each is connected to. This is a very convenient representation.

A common type of graph in computer science are grids, in which nodes are laid in a grid, and they are connected to the nodes selected top, bottom, left and right.

Binary trees

A tree is a graph in which there is only one path between every pair of nodes. Some concepts related to trees are: root, the (only) node on level 1; parent, the connected node in the level above; child, a connected in the level below; and leaf, a node with no children. Importantly, a tree has only one root. A very useful type of tree are binary trees, in which every node has at most two children.

Often trees are represented using classes. Specifically, we would have an object Node like:

class Node:

def __init__(self, val=None):

self.val = val

self.left = None

self.right = None

We would keep a reference to the root, and build a try by successively creating new nodes and assigning them to .left or .right.

Heaps / priority queues

(Min-)Heaps are binary trees in which the value of every parent is lower or equal than any of its children. This gives them their most interesting property: the minimum element is always on top. (Similarly, in max-heaps, the maximum stands at the root.) Because of that, they are also called priority queues. A famous algorithm that can be solved with heaps is computing the running median of a data stream.

In Python, heapq provides an implementation of the heap. Any populated list can be transformed in-place into a heap:

import heapq

x = [5, 123, 8, 3, 2, 6, -5]

heapq.heapify(x)

[-5, 2, 5, 3, 123, 6, 8]

The elements have been reordered to represent a heap: each parent note is indexed by \(k\), and its children by \(2k+1\) and \(2k+2\).

Let’s see some common operations:

-

Push a new element (and sift up):

heapq.heappush(x, -10) print(x)[-10, -5, 5, 2, 123, 6, 8, 3] -

Pop the root (and sift down):

heapq.heappop(x)-10 -

Combine the two operations:

- Push, then pop:

heapq.heappushpop(x, -7) # [-5, 2, 5, 3, 123, 6, 8]-7 - Pop, then push:

heapq.heapreplace(x, -7) # [-7, 2, 5, 3, 123, 6, 8]-5

- Push, then pop:

Let’s examine the time complexity of each operation:

- Creation: \(O(n)\)

- Update: \(O(\log n)\)

- Min/max retrieval: \(O(1)\)

Note: Heaps are great to recover the smallest element, but not the kth smallest one. BSTs might me more appropriate for that.

Binary search trees

Binary serach trees (BSTs) are binary trees in which every node meets two properties:

- All descendants on the left are smaller than the parent node.

- All descendants on the right are larger than the parent node.

They provide a good balance between insertion and search speeds:

- Search: done recursively on the tree. When balanced, search is as good as binary search on a sorted array.

- Insertion: also done recursively, by traversing the tree from the root in order until we find an appropriate place.

The time complexity of both is \(O(\log n)\) when the tree is balanced; otherwise it is \(O(n)\). (Balanced trees are those whose height is small compared to the number of nodes. Visually, they look full and all branches look similarly long.) As a caveat, no operation takes constant time on a BST.

Tries

Tries (from retrieval) are trees that store strings:

- Nodes represent characters, except for the root, represents the string start.

- Children represent each of the possible characters that can follow the parent.

- Leaf nodes represent the end of the string.

- Paths from the root to the leafs represent the different words.

Due to its nature, tries excel at two things:

- Saving space when storing words sharing the same prefix, since they only store the prefix once.

- Searching words, which can be done in \(O(\text{word length})\). Similarly, they make it very fast to search for words with a given prefix.

These two properties make them excellent at handling spell checking and autocomplete functions.

Union-finds

Union-finds, also known as Disjoint-sets, store a collection of non-overlapping sets. Internally, sets are represented as directed trees, in which every member points towards the root of the tree. The root is just another member, which we call the representative. Union-finds provide two methods:

- Find: returns the set an element belongs to. Specifically, it returns its representative.

- Union: combines two sets. Specifically, first, it performs two finds. If the representatives differ, it will connect one tree’s root to the root of the other.

Union-finds can be represented as an array, in which every member of the universal set is one element. Members linked to a set take as value the index of another member of the set, often the root. Consequently, members that are the only members of a set take their own value. The same goes for the root. While this eliminates many meaningful pairwise relationship between the elements, it speeds up the two core operations.

Every set has a property, the rank, which approximates its depth. Union is performed by rank: the root with the highest rank is picked as the new root. Find performs an additional step, called path compresion, in which every member in the path to the root will be directly bound to the root. This increases the cost of that find operation, but keeps the tree shallow and the paths short, and hence speeds up subsequent find operations.

Here is a Python implementation:

class UnionFind:

def __init__(self, size):

self.parent = [i for i in range(size)]

self.rank = [0] * size

def find(self, x):

if self.parent[x] != x:

self.parent[x] = self.find(self.parent[x]) # Path compression

return self.parent[x]

def union(self, x, y):

rootX = self.find(x)

rootY = self.find(y)

if rootX != rootY:

if self.rank[rootX] > self.rank[rootY]:

self.parent[rootY] = rootX

self.rank[rootX] = self.rank[rootY]

else:

self.parent[rootX] = rootY

self.rank[rootY] = self.rank[rootX]

Probabilistic data structures

Bloom filters

Bloom filters are data structures to probabilistically check if an element is a member of a set. It can be used when false positives are acceptable, but false negatives are not. For instance, if we have a massive data set, and we want to quickly discard all the elements that are not part of a specific set.

The core structure underlying bloom filters is a bit array, which makes it highly compact in memory. When initialized, all the positions are set to 0. When inserting a given element, we apply multiple hash functions to it, each of which would map the element to a bucket in the array. This would be the element’s “signature”. Then, we would set the value of each of these buckets to 1. To probabilistically verify if an element is in the array, we would compute its signature and examine if all the buckets take a value of 1.

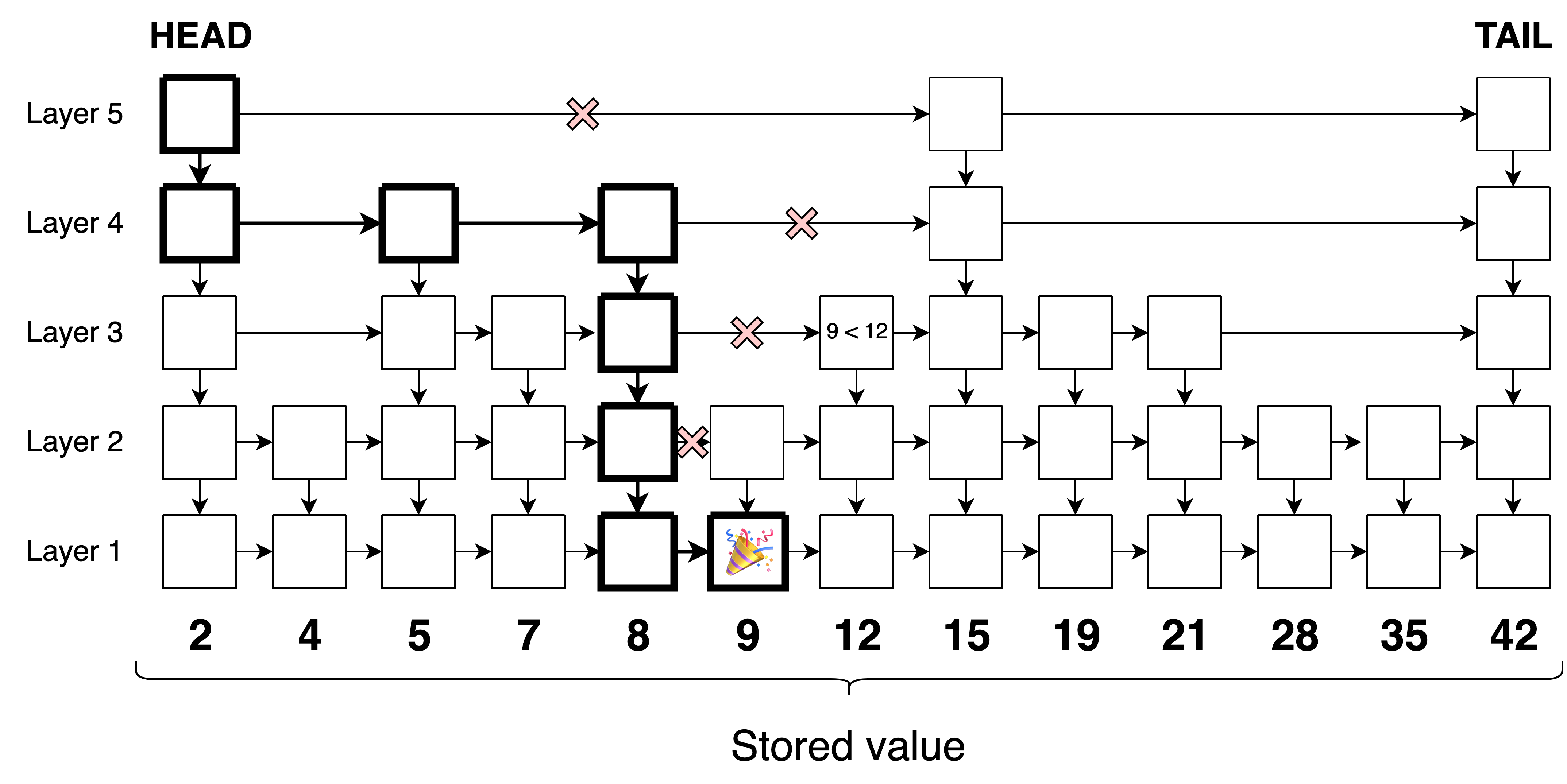

Skip lists

Skip lists are a data structure consisting of a set of linked lists, each one containing a subset of the items in the collection:

The topmost list contains only a few items, while the bottommost list contains all the items. Each item in a list points to the next item in the same list, and also to the next item in the lists below it. This allows us to quickly traverse the lists and find or insert items in logarithmic time with high probability:

def find_entry(node, query_number):

if node.right and node.right.value < query_number:

# keep moving right whenever possible

return find_entry(node.right, query_number)

elif node.down:

# move down when we can't move right anymore

return find_entry(node.down, query_number)

else:

# we are at the bottom layer

if node.right and node.right.value == query_number:

return node.right

else:

# not found

return None

Linked lists

A linked list is a DAG in which almost every node has exactly one inbound edge and one outbound edge. The exceptions are the head, a node with no inbound egde, and the tail, a node with no outbound edge. Like arrays, linked lists are ordered. However, they have one key diference: insertions in the middle of an array are expensive (\(O(n)\)), since they require copying all the items of the array, while they are cheap in the linked list (\(O(1)\)), since they only require changing two pointers.

This is an implementation of a linked list:

class Node:

def __init__(self, val):

self.val = val

self.next = None

a = Node("A")

b = Node("B")

c = Node("C")

d = Node("D")

a.next = b

b.next = c

c.next = d